- Home

- Douglas Murray

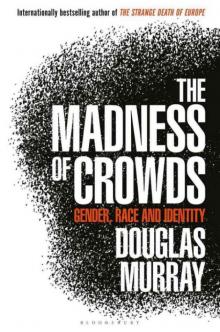

The Madness of Crowds

The Madness of Crowds Read online

Contents

Introduction

1 Gay

Interlude– The Marxist Foundations

2 Women

Interlude– The Impact of Tech

3 Race

Interlude– On Forgiveness

4 Trans

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

Notes

Index

‘The special mark of the modern world is not that it is sceptical, but that it is dogmatic without knowing it.’

G. K. Chesterton

‘Oh my gosh, look at her butt

Oh my gosh, look at her butt

Oh my gosh, look at her butt

(Look at her butt)

Look at, look at, look at

Look, at her butt’

N. Minaj

Introduction

We are going through a great crowd derangement. In public and in private, both online and off, people are behaving in ways that are increasingly irrational, feverish, herd-like and simply unpleasant. The daily news cycle is filled with the consequences. Yet while we see the symptoms everywhere, we do not see the causes.

Various explanations have been given. These tend to suggest that any and all madnesses are the consequence of a Presidential election, or a referendum. But none of these explanations gets to the root of what is happening. For far beneath these day-to-day events are much greater movements and much bigger events. It is time we began to confront the true causes of what is going wrong.

Even the origin of this condition is rarely acknowledged. This is the simple fact that we have been living through a period of more than a quarter of a century in which all our grand narratives have collapsed. One by one the narratives we had were refuted, became unpopular to defend or impossible to sustain. The explanations for our existence that used to be provided by religion went first, falling away from the nineteenth century onwards. Then over the last century the secular hopes held out by all political ideologies began to follow in religion’s wake. In the latter part of the twentieth century we entered the postmodern era. An era which defined itself, and was defined, by its suspicion towards all grand narratives.1 However, as all schoolchildren learn, nature abhors a vacuum, and into the postmodern vacuum new ideas began to creep, with the intention of providing explanations and meanings of their own.

It was inevitable that some pitch would be made for the deserted ground. People in wealthy Western democracies today could not simply remain the first people in recorded history to have absolutely no explanation for what we are doing here, and no story to give life purpose. Whatever else they lacked, the grand narratives of the past at least gave life meaning. The question of what exactly we are meant to do now – other than get rich where we can and have whatever fun is on offer – was going to have to be answered by something.

The answer that has presented itself in recent years is to engage in new battles, ever fiercer campaigns and ever more niche demands. To find meaning by waging a constant war against anybody who seems to be on the wrong side of a question which may itself have just been reframed and the answer to which has only just been altered. The unbelievable speed of this process has been principally caused by the fact that a handful of businesses in Silicon Valley (notably Google, Twitter and Facebook) now have the power not just to direct what most people in the world know, think and say, but have a business model which has accurately been described as relying on finding ‘customers ready to pay to modify someone else’s behaviour’.2 Yet although we are being aggravated by a tech world which is running faster than our legs are able to carry us to keep up with it, these wars are not being fought aimlessly. They are consistently being fought in a particular direction. And that direction has a purpose that is vast. The purpose – unknowing in some people, deliberate in others – is to embed a new metaphysics into our societies: a new religion, if you will.

Although the foundations had been laid for several decades, it is only since the financial crash of 2008 that there has been a march into the mainstream of ideas that were previously known solely on the obscurest fringes of academia. The attractions of this new set of beliefs are obvious enough. It is not clear why a generation which can’t accumulate capital should have any great love of capitalism. And it isn’t hard to work out why a generation who believe they may never own a home could be attracted to an ideological world view which promises to sort out every inequity not just in their own lives but every inequity on earth. The interpretation of the world through the lens of ‘social justice’, ‘identity group politics’ and ‘intersectionalism’ is probably the most audacious and comprehensive effort since the end of the Cold War at creating a new ideology.

To date ‘social justice’ has run the furthest because it sounds – and in some versions is – attractive. Even the term itself is set up to be anti-oppositional. ‘You’re opposed to social justice? What do you want, social injustice?’

‘Identity politics’, meanwhile, has become the place where social justice finds its caucuses. It atomizes society into different interest groups according to sex (or gender), race, sexual preference and more. It presumes that such characteristics are the main, or only, relevant attributes of their holders and that they bring with them some added bonus. For example (as the American writer Coleman Hughes has put it), the assumption that there is ‘a heightened moral knowledge’ that comes with being black or female or gay.3 It is the cause of the propensity of people to start questions or statements with ‘Speaking as a . . .’. And it is something that people both living and dead need to be on the right side of. It is why there are calls to pull down the statues of historical figures viewed as being on the wrong side and it is why the past needs to be rewritten for anyone you wish to save. It is why it has become perfectly normal for a Sinn Fein senator to claim that the IRA hunger strikers in 1981 were striking for gay rights.4 Identity politics is where minority groups are encouraged to simultaneously atomize, organize and pronounce.

The least attractive-sounding of this trinity is the concept of ‘intersectionality’. This is the invitation to spend the rest of our lives attempting to work out each and every identity and vulnerability claim in ourselves and others and then organize along whichever system of justice emerges from the perpetually moving hierarchy which we uncover. It is a system that is not just unworkable but dementing, making demands that are impossible towards ends that are unachievable. But today intersectionality has broken out from the social science departments of the liberal arts colleges from which it originated. It is now taken seriously by a generation of young people and – as we shall see – has become embedded via employment law (specifically through a ‘commitment to diversity’) in all the major corporations and governments.

New heuristics have been required to force people to ingest the new presumptions. The speed at which they have been mainstreamed is staggering. As the mathematician and writer Eric Weinstein has pointed out (and as a Google Books search shows), phrases like ‘LGBTQ’, ‘white privilege’ and ‘transphobia’ went from not being used at all to becoming mainstream. As he wrote about the graph that results from this, the ‘woke stuff’ that Millennials and others are presently using ‘to tear apart millennia of oppression and /or civilization . . . was all made up about 20 minutes ago’. As he went on, while there is nothing wrong with trying out new ideas and phrases, ‘you have to be pretty damn reckless to be leaning this hard on so many untested heuristics your parents came up with in untested fields that aren’t even 50 years old’.5 Similarly, Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt have pointed out (in their 2018 book The Coddling of the American Mind) how new the means of policing and enforcing these new heuristics have become. Phrases like ‘triggered’ and ‘feeling unsafe’ an

d claims that words that do not fit the new religion cause ‘harm’ only really started to spike in usage from 2013 onwards.6 It is as though, having worked out what it wanted, the new metaphysics took a further half-decade to work out how to intimidate its followers into the mainstream. But it has done so, with huge success.

The results can be seen in every day’s news. It is behind the news that the American Psychological Association feels the need to advise its members on how to train harmful ‘traditional masculinity’ out of boys and men.7 It is why a previously completely unknown programmer at Google – James Damore – can be sacked for writing a memo suggesting that some jobs in tech appeal more to men than they do to women. And it is why the number of Americans who view racism as a ‘big problem’ doubled between 2011 and 2017.8

Having begun to view everything through the new lenses we have been provided with, everything is then weaponized, with consequences which are deranged as well as dementing. It is why The New York Times decides to run a piece by a black author with the title: ‘Can my Children be Friends with White People?’9 And why even a piece about cycling deaths in London written by a woman can be framed through the headline: ‘Roads Designed by Men are Killing Women’.10 Such rhetoric exacerbates any existing divisions and each time creates a number of new ones. And for what purpose? Rather than showing how we can all get along better, the lessons of the last decade appear to be exacerbating a sense that in fact we aren’t very good at living with each other.

For most people some awareness of this new system of values has become clear not so much by trial as by very public error. Because one thing that everybody has begun to at least sense in recent years is that a set of tripwires have been laid across the culture. Whether placed by individuals, collectives or some divine satirist, there they have been waiting for one person after another to walk into them. Sometimes a person’s foot has unwittingly nicked the tripwire and they have been immediately blown up. On other occasions people have watched some brave madman walking straight into the no man’s land, fully aware of what they were doing. After each resulting detonation there is some disputation (including the occasional ‘coo’ of admiration) and then the world moves on, accepting that another victim has been notched up to the odd, apparently improvisatory value system of our time.

It took a little while for the delineation of these tripwires to become clear, but they are clear now. Among the first was anything to do with homosexuality. In the latter half of the twentieth century there was a fight for gay equality which was tremendously successful, reversing terrible historic injustice. Then, the war having been won, it became clear that it wasn’t stopping. Indeed it was morphing. GLB (Gay, Lesbian, Bi) became LGB so as not to diminish the visibility of lesbians. Then a T got added (of which much more anon). Then a Q and then some stars and asterisks. And as the gay alphabet grew, so something changed within the movement. It began to behave – in victory – as its opponents once did. When the boot was on the other foot something ugly happened. A decade ago almost nobody was supportive of gay marriage. Even gay rights groups like Stonewall weren’t in favour of it. A few years down the road and it has been made into a foundational value of modern liberalism. To fail the gay marriage issue – only years after almost everybody failed it (including gay rights groups) – was to put yourself beyond the pale. People may agree with that rights claim, or disagree, but to shift mores so fast needs to be done with extraordinary sensitivity and some deep thought. Yet we seem content to steam past, engaging in neither.

Instead, other issues followed a similar pattern. Women’s rights had – like gay rights – been steadily accumulated throughout the twentieth century. They too appeared to be arriving at some sort of settlement. Then just as the train appeared to be reaching its desired destination it suddenly picked up steam and went crashing off down the tracks and into the distance. What had been barely disputed until yesterday became a cause to destroy someone’s life today. Whole careers were scattered and strewn as the train careered along its path.

Careers like that of the 72-year-old Nobel Prize-winning Professor Tim Hunt were destroyed after one lame joke, at a conference in South Korea, about men and women falling in love in the lab.11 Phrases such as ‘toxic masculinity’ entered into common use. What was the virtue of making relations between the sexes so fraught that the male half of the species could be treated as though it was cancerous? Or the development of the idea that men had no right to talk about the female sex? Why, when women had broken through more glass ceilings than at any time in history, did talk of ‘the patriarchy’ and ‘mansplaining’ seep out of the feminist fringes and into the heart of places like the Australian Senate?12

In a similar fashion the civil rights movement in America, which had started in order to right the most appalling of all historic wrongs, looked like it was moving towards some hoped-for resolution. But yet again, near the point of victory everything seemed to sour. Just as things appeared better than ever before, the rhetoric began to suggest that things had never been worse. Suddenly – after most of us had hoped it had become a non-issue – everything seemed to have become about race. As with all the other tripwire issues, only a fool or a madman would think of even speculating – let alone disputing – this turnaround of events.

Then finally we all stumbled, baffled, into the most unchartered territory of all. This was the claim that there lived among us a considerable number of people who were in the wrong bodies and that as a consequence what certainties remained in our societies (including certainties rooted in science and language) needed to be utterly reframed. In some ways the debate around the trans question is the most suggestive of all. Although the newest of the rights questions also affects by far the fewest number of people, it is nevertheless fought over with an almost unequalled ferocity and rage. Women who have got on the wrong side of the issue have been hounded by people who used to be men. Parents who voice what was common belief until yesterday have their fitness to be parents questioned. In the UK and elsewhere the police make calls on people who will not concede that men can be women (and vice versa).13

Among the things these issues all have in common is that they have started as legitimate human rights campaigns. This is why they have come so far. But at some point all went through the crash barrier. Not content with being equal, they have started to settle on unsustainable positions such as ‘better’. Some might counter that the aim is simply to spend a certain amount of time on ‘better’ in order to level the historical playing field. In the wake of the #MeToo movement it became common to hear such sentiments. As one CNN presenter said, ‘There might be an over-correction, but that’s OK. We’re due for a correction.’14 To date nobody has suggested when over-correction might have been achieved or who might be trusted to announce it.

What everyone does know are the things that people will be called if their foot even nicks against these freshly laid tripwires. ‘Bigot’, ‘homophobe’, ‘sexist’, ‘misogynist’, ‘racist’ and ‘transphobe’ are just for starters. The rights fights of our time have centred around these toxic and explosive issues. But in the process these rights issues have moved from being a product of a system to being the foundations of a new one. To demonstrate affiliation with the system people must prove their credentials and their commitment. How might somebody demonstrate virtue in this new world? By being ‘anti-racist’, clearly. By being an ‘ally’ to LGBT people, obviously. By stressing how ardent your desire is – whether you are a man or a woman – to bring down the patriarchy.

And this creates an auditioning problem, where public avowals of loyalty to the system must be volubly made whether there is a need for them or not. It is an extension of a well-known problem in liberalism which has been recognized even among those who did once fight a noble fight. It is a tendency identified by the late Australian political philosopher Kenneth Minogue as ‘St George in retirement’ syndrome. After slaying the dragon the brave warrior finds himself stalking the land looking for still more gl

orious fights. He needs his dragons. Eventually, after tiring himself out in pursuit of ever-smaller dragons he may eventually even be found swinging his sword at thin air, imagining it to contain dragons.15 If that is a temptation for an actual St George, imagine what a person might do who is no saint, owns no horse or lance and is being noticed by nobody. How might they try to persuade people that, given the historic chance, they too would without question have slain that dragon?

In the claims and supporting rhetoric quoted throughout this book there is a good deal of this in evidence. Our public life is now dense with people desperate to man the barricades long after the revolution is over. Either because they mistake the barricades for home, or because they have no other home to go to. In each case a demonstration of virtue demands an overstating of the problem, which then causes an amplification of the problem.

But there is more trouble in all of this, and it is the reason why I take each of the bases of these new metaphysics not just seriously but one by one. With each of these issues an increasing number of people, having the law on their side, pretend that both their issue and indeed all these issues are shut down and agreed upon. The case is very much otherwise. The nature of what is meant to be agreed upon cannot in fact be agreed upon. Each of these issues is infinitely more complex and unstable than our societies are currently willing to admit. Which is why, put together as the foundation blocks of a new morality and metaphysics, they form the basis for a general madness. Indeed a more unstable basis for social harmony could hardly be imagined.

For while racial equality, minority rights and women’s rights are among the best products of liberalism, they make the most destabilizing foundations. Attempting to make them the foundation is like turning a bar stool upside down and then trying to balance on top of it. The products of the system cannot reproduce the stability of the system that produced them. If for no other reason than that each of these issues is a deeply unstable component in itself. We present each as agreed upon and settled. Yet while the endless contradictions, fabrications and fantasies within each are visible to all, identifying them is not just discouraged but literally policed. And so we are asked to agree to things which we cannot believe.

The Madness of Crowds

The Madness of Crowds